Construction

Planning

Triangulation

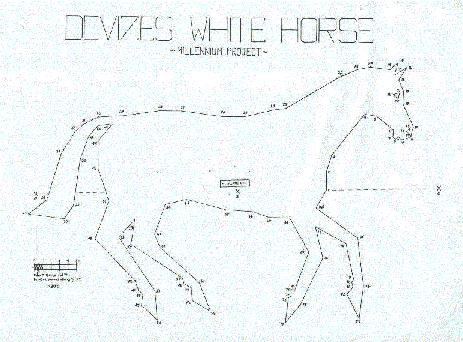

There have been many methods of transposing hillfigure plans from paper to the hillside, George Marples method involved the accurate location (by surveying) of three points on the hillside in close proximity to the figure, from these all the points of the horse could be triangulated. This method was the same as that used on the recent Devizes horse construction except that GPS was used for the accurate location of the three points. This is a very accurate method of transposing the plan.

George Marples Plan

Peter Greed's Devizes White Horse Plan

The Grid System

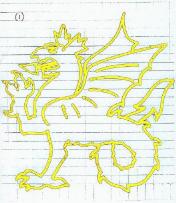

The Charlton Wyvern construction takes on a grid type approach, the plan is divided into a grid and this grid is marked up on the hillside and the figure cut a square at a time according to the plan. The method is not as accurate as triangulation but allows the gradual construction and construction of a large figure by one person.

Charlton Wyvern Plan

Trial and Error

This is the trial and error method which is directed from afar. This method was used for the Folkestone mockup recently. The tarpaulin was unfolded on the hill, and positioned as per the directions given afar by mobile phone/walkie talkies in this case but by shouting and megaphone in the past.

Folkestone Whitehorse Plan

Projection

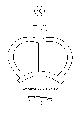

A variation of the trial and error method was used to construct the Wye crown. The crown design was taken from a florin, cut into paper and pasted onto a theodolite object lens - to appear as if it was on the hill, hand signals were used to guide the marking out of the edge of this image from the distant point.

Wye Crown Plan

Construction

Until recently there were three methods for hillfigure construction which are usually dependant on the depth of the soil above the underlying chalk and the general site of the figure are:

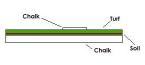

1. Stripping:- where the soil is thin, the turf / soil is stripped away exposing the underlying chalk. This method produces quick results but the figure need lots of maintenance and is easily overgrown, only a few figures are of this type e.g. Laverstock Panda - now lost. Traces of figures of this type are not usually found after the figure is overgrown.

2. Covering:- this is the simplest method where rocks are placed on top of the turf. This is usually carried out where there is no underlying chalk, the chalk is deep or if the figure needs to be constructed quickly, tools are not available etc., maintenance is very high. There are several examples of this type, e.g. Woolbury Horse. This method leaves no trace of the figures existence when overgrown, as is the case of the lost Fovant Badges.

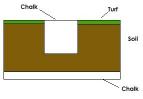

3. Trenching:- this is by far the most common method of hillfigure construction. The underlying chalk where some hillfigures are constructed is not near the surface so a trench is dug and chalk from another site is used to fill the trench. The Uffington White Horse is the prime example of this method. This was the method originally to be used for the new Devizes Horse. This method is invasive in the hillside and allows traces of the figure to be seen even when the figure has been overgrown for many years. The Snobs horse was constructed this way and this is why traces of it can still be seen today.

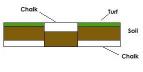

On the recent Devizes white horse construction a novel method was used, this is known as Double digging.

The process is as follows :- Some of the top soil was removed from the body of the figure and then chalk is cut from within the body of the figure. Working entirely within the bounds of the body of the figure, chalk is excavated from within, topsoil infilled, and the chalk placed on the top and compacted. This method saves on disposal of the earth removed, the need for fresh chalk excavation elsewhere and the associated costs and effort. The downsides are that the chalk is not always of the pure white archaeological grade usually used for hill figures and the figure may not be as white as some of the other figures.

Materials

I keep using the word chalk but not all hillfigures are chalk, there are many other different materials used for hillfigure construction, but all use are constructed using the methods described above.

Loam Soil:-Red Horses of Tysoe,

Sandstone:- Part of Battle of Britain Memorial (Rest Brick Formerly Chalk)

Granite:- Dover Aeroplane

Quartz:- Strichen Horse and Stag

Flint:- Woolbury White Horse

Cement:- Westbury White Horse

Limestone:- Kilburn White Horse

Foreshortening

What is foreshortening, and how does it affect hillfigure construction?

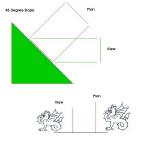

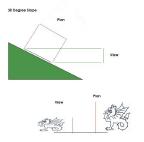

Three hillsides will illustrate foreshortening, the red line is the plan view which is constant, the green line is the view from the ground.

On a 45° slope, the effect is evident. The green line is a little shorter than the red line and the hillfigure would appear to be squashed, this is the foreshortening effect.

On a 30° slope this effect is even worse, the green line is now much shorter than the red line and the figure is really squashed.

On a 60° slope, the diagram the red line is how the hillfigure would appear on the plan, or from the air. The green line indicates how it would be seen from the ground. They are both similar length and therefore there is no noticeable foreshortening.

As shown the effect of foreshortening is greatest on gentle slopes like Devizes and hardly noticed on a steep slope such as Westbury or Kilburn, this has to be taken into account when designing hillfigures.

Classification

Rock Art can be classified into three types.

Petroglyphs

Images carved or pecked into a rock face using stone tools. Human-like (anthropomorphic), animal and bird (zoomorphic) images are common, as are circles, spirals, dots, lines, and other geometric and abstract forms.

Pictographs

Pictographs are images painted on a rock face. The paints were typically made from pulverised minerals, so red, white and black are the most common colours.

Geoglyphs

These are images formed in the ground. Typically surface matter was scraped away to form an image in the exposed, underlying soil, or by arranging stones to form an image. Geoglyphs are the most fragile rock art. Hillfigures are are a subsection of geoglyphs.

Hillfigures

A subset of Geoglyphs, hillfigures are effigies cut into the chalk hillside mainly in Southern England ther are several examples in the other parts of the UK and a handful in the rest of the world. Most are horses.

Alternative, colloquial and related terms: Gogmagog; Long man; Red horse; White horse

Ordnance Survey map term: Hillfigure.

RCHME Thesuarus Monument Type : Hill Figure.

Definition

A hill figure is a large scale visual representation of some kind of symbol or design or motif, often in human or animal form, which has been created as described above to provide a contrast to the surrounding turf. They are usually more easy to see from some distance away.

Some examples are obvious white figures in chalk or limestone which have been kept scoured and have not become overgrown. Those that are not kept clean may be recognised either as slight indentations from close up or in outline from a distance when there is a small quantity of snow on the ground or in dry periods when they occur as "soil marks", this can be aided with the use of aerial photography and camera filters, as described on the dating and discovery page. They vary in size up to 60m tall.

Hillfigures are unlikely to be confused with any other category of monument, as they are quite distinctive. Fungus rings and natural features may complicate the recognition of the hillfigure if not lead to its misidentification.

They are often interpreted as religious and ritual symbols, representing gods, or as places for fertility rites. More recently hill figures have been carved for advertising, for example the Whipsnade lion, or as memorials such as the emblems on Fovant Down. They therefore vary considerably in date from the Iron Age to the 20th century. The newest figure was cut in 1999.

Date

There are as yet no radiocarbon dates from hill figures. Excavation has produced limited artefactual dating evidence, as at The Long Man of Wilmington hill figure in Sussex, where possible Roman fired clay fragments were produced. eighteenth and nineteenth centuries hill figures have been dated by documentary evidence. Letters have been discovered which date the first cutting of the white horse near Litlington, East Sussex to 1836 by James Pagden, a farmer and his brothers. A terminus ante quem for some hill figures is provided by the first documentary evidence recognising their existence. In this way the Cerne Abbas Giant, Dorset, is dated prior to the mid 18th century and the Uffington horse, Berkshire to before the 17th century, when an obligation to scour the horse of weeds was first placed on the tenants of the neighbouring manors. Although this obligation was first recorded in the 17th century it may date from the 9th/10th century laying out of the open fields. Dating is therefore often insecure, particularly where a monument has been altered several times. Overall the currency of the tradition probably extends from the Iron Age to the present day, a total duration of perhaps two millennia.

Attempts have been made to date hill figures typologically by their relation to figures on other materials, for example coins, and by association with nearby monuments. It was for this reason that many hill figures were initially ascribed a Bronze Age date as they often occur near barrows, or an Iron Age date because of finds of Iron Age coins nearby.

Many such monuments have been used up to the present day as places of worship/ ritual activity. The Long Man of Wilmington, Sussex was restored in 1874 when the outline of the figure was built in brick, and then in 1969 this was replaced by concrete blocks. It has been suggested that the left leg and foot were turned around in the 1874 restoration and other details altered. The White Horse of Litlington, Sussex, was changed as recently as 1983, when in attempt to prevent erosion and to give greater definition to the legs the foreleg was raised.

There is no evidence for early phases of the tradition but more recent trends can be seen as at the White Horse near Litlington which was first cut in 1836 and recut in 1924 and for which records and drawings survive.

Folklore often surrounds hillfigures and has played some part in the dating of hill figures, though it is not possible to assess with what success as the pre 1700 hill figures are insecurely dated anyway.

The only accurate dating of a hillfigure that was not recorded is that of the Uffington White Horse by Optical Stimulated Luminescence, providing a date of circa. 1200BC.

General Description

There are records of hill figures as early as the 17th century. Sir Flinders Petrie wrote the first collective study of hill figures in England in 1926. This was followed by the work of M. Marples in 1949. The most recent surveys are the hillfigure home page which has the only complete and upto date reference of hillfigures in the UK. Excavation and survey work has been very limited and relatively little is known of figures dating prior to 1700. A few specific examples have been studied more recently as, for example, the Cerne Abbas Giant by Grinsell and the Uffington Horse by the Oxford Archaeological unit.

Hill figures vary in size from 15m to 60m tall and represent a variety of shapes and forms human, animal and artefactual and symbolic. It is possible that some once covered whole hillsides, for example at Wandlebury near Cambridge and Tysoe, Warwickshire, though the evidence so far produced here is somewhat spurious.

Entrenchments are the method by which the subsoil was revealed beneath the turf to form the figure. This might be in outline, such as the Cerne Abbas Giant, Dorset,. Alternatively the whole of the figure may have been removed as at Uffington horse in Oxfordshire, where the outline is created by the edge of the surrounding turf and not the subsoil.

Subsoil of which the figure is composed is in most cases chalk, though the figures at Tysoe are of red clay and in Yorkshire the Kilburn Horse is made from limestone, the Mormond figures are of quartz, the Bleriot memorial granite, the Battle of Britain memorial brick, the Westbury Horse and Long Man of Wilmington concrete.

The means by which the design was transferred to the hillside in the more ancient hill figures is not known. The Litlington horse, Sussex was laid out with pegs and ropes and sticks. More recent examples have used a variety of techniques including loud halers and two-way radio systems from neighbouring hills to co-ordinate the operation. One example involved sticking a paper shape of the figure to the object lens of a theodolite while people holding flagged poles were directed with hand signals around the outline on the hillside. More details above in the construction section.

Six main types of hill figures have been identified on the basis of date and what they represent (Figure 1) :

A: Horses carved into the subsoil, either chalk or clay and usually with a turf outline, and completely composed of subsoil within. They have been variously assigned Iron Age to Saxon dates. (For example, The Uffington Horse, Oxfordshire).

B: Crosses carved into the hillside and usually represented as sitting on a plinth or hillside. Two in the Chilterns have been associated with monkish conclaves of Risborough and Misenden, both of which lie in the near vicinity and probably date to the Saxon period. The cross at Ditchling, Sussex is associated with the battle of Lewes, 1284, and is probably 13th-14th century in date. (For example, Whiteleaf, Chiltern Hills).

C: Giants, carved in outline into the subsoil. They have generally suffered later modifications and only two survive in situ today. These are the Cerne Abbas and Long Man of Wilmington giants in Dorset and Sussex respectively. Resistivity surveys have suggested that they may have had extra features originally. (For example, Cerne Abbas Giant, Dorset). D: Military Badges, both in chalk and turf outlines often crudely constructed and sometimes shortlived the oldest from 1916. (for example, Fovant Down Military Bagdes).

E: Modern miscellaneous hill figure designs, both in chalk and turf outlines and representing a variety of things, including animals, a crown and an aeroplane. They date to the 20th century. (For example, Whipsnade Lion, Herts).

F: Complex designs on whole hillsides which involve more than one figure. For example, at Wandlebury, cambridgeshire there may be several figures, two horses with a female rider, and two giants. These are the somewhat subjective results of partial excavation, soundings and aerial survey as at Glastonbury, Somerset and Tysoe, Warwickshire and are only tentatively included as a type of hill figure. (For example, Wandlebury, Cambridgeshire).

Several hill figures had more than one phase of activity. The Westbury horse in Wiltshire was remodelled in 1778. There may have been up to five red horses at Tysoe, Warwickshire, all of which have now been lost. Resistivity surveys at Cerne Abbas, Dorset and the Long Man of Wilmington, Sussex have indicated the presence of features which are no longer visible. Grinsell detected changes in the anatomy in the Cerne Abbas Giant, which he thought reflected a change in taste in the Victorian period. At Uffington traces of many legs and necks of the horse in different positions have been found.

There are no obviously associated features near hill figures which have been found which might indicate function, but excavation may well produce some. They have generally been interpreted as the religious symbols of gods or as sites for ritual acts and significant calendrical events. They may also be property markers, a function which has been suggested for the crosses on the Chiltern scarp. The figures at Plymouth and the Gogmagog hills, Cambridge, have been explained as welcoming or warning signs near significant sites. Alternatively they may have been built to occupy people's time, as for example happened at Bulford, Wiltshire at the end of the first World War, when New Zealand troops, waiting to go home carved a kiwi into the hillside. Alternatively, they may be commemorative, as the aeroplane at Dover or the Wye Crown in Kent which was built to commemorate the silver jubilee of George V, or the panda at Laverstock, Wiltshire, constructed in 1969 as a student prank. Some of the 18th century white horses were doubtless constructed as fakes as well as follies.

Distribution and regional variation

Hill figures are largely confined to the Southern England, especially to the chalklands of Wiltshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Kent and Sussex, with a couple of examples in Warwickshire, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire, Buckhamshire and Dorset. There is one example in Yorkshire, three examples in Scotland and one in Wales.

They cluster especially in Wiltshire, where most of the examples are 18th century onwards and nearly all are representations of horses. Individual types sometimes occur in pairs or groups.

Rarity

The exact number of hill figures that have existed is not known with certainty, but is probably between 70 and 100. It is likely that more existed, lasting perhaps into the Middle Ages, but only a few records remain of some which were visible then. Many have probably been destroyed or become overgrown. The recorded number is unlikely to be a realistic reflection of the number carved in ancient times although most of the recent ones survive. Currently 43 figures can be seen and there have been 28 lost that are documented or that there is evidence for.

Survival and Potential

Figures marked in outline only, such as the Uffington horse and the Cerne and Wilmington Giants, all of some antiquity, have survived best, not least because they have been kept scoured. Erosion, undergrowth, and disturbance by rabbit warrrens and water channels are contributary factors in obscuring hillfigures.

Excavation has been limited to trial trenches and soundings at Wandlebury, Cambridgeshire and limited excavation in advance of restoration work at the Long Man of Wilmington, Sussex. The latter produced no evidence of construction or date other than some questionable Roman fired clay fragments. Excavations at Wandlebury produced some tentative evidence to suggest the existence of more than one hill figure. Unfortunately the remainder of the investigations there consisted only of soundings and are not generally accredited any certainty.

Resistivity surveys have been carried out at the sites of the Cerne Abbas Giant in Dorset and the Long Man of Wilmington, Sussex to determine if there was any other earlier features hidden beneath the turf. There is some suggestion that the Cerne Abbas Giant wore a bear-skin. Earlier sketches of the Long Man had depicted a scythe and rake in his hands instead of the two rods which are now visible. Resistivity survey and infra-red photography picked up anomalies in these areas, but the results were not conclusive. It is also possible that the figure was helmeted and had a plume. It has been shown that the left leg and foot of the giant have been turned around, probably during the 1874 restoration.

Potentially important contexts include possible buried land surfaces beneath the carving for environmental evidence. Excavation around the figures might reveal associated features such as pathways, pits, deposits and timber structures. Any burnt material which might be used for dating purposes and the fill of the cut for evidence of function will be important.

Antiquarian records are sometimes the only records extant of hill figures. These may consist of letters, descriptions and drawings and occasionally old photographs as well as more flowery poetry and accounts of annual scourings of the monuments by villagers to preserve them. There is a wealth of folklore associated with hill figures to which some truth might be assigned, concerning rituals carried out by locals at these monuments.

Associations

Hill figures have a limited range of spatial associations with other monument classes including round and long barrows, lynchets, Iron Age hillforts, quarries and flint mines. It is not known if these other monuments are contemporary or not, though buildings and farms dating back to the last century may well have been directly associated with the people who built the more recent examples.

Characterization criteria

The four criteria for assessing class importance apply to hill figures as follows:

Period (currency): Long-lived. The tradition of carving of hill figures probably started in the late Neolithic / Iron Age and continued through to the present day, a total duration of three millennia.

Rarity: Very rare. About 43 examples are currently known, although a programme of aerial photography might reveal more which belong to the class.

Diversity (form): High. Six types have been identified on the basis of the date of the monument and the form it depicted.

Period (representativity): Low. Hill figures are one of several classes of prehistoric, mediaeval, and Middle Ages and later monuments. They are quite well scattered in the south and were probably locally important monuments, judging from the period of time over which they were used.

Assigning scores to these criteria following the system set out in the Monument Evaluation Manual, hill figures yield a Class Importance Value of 42. This lies two thirds of the way up the range of possible values (max. = 64), reflecting the long currency and rarity of the class. Examples representing the main types, a range of locations and those not yet disturbed should be included in the sample of nationally important sites.